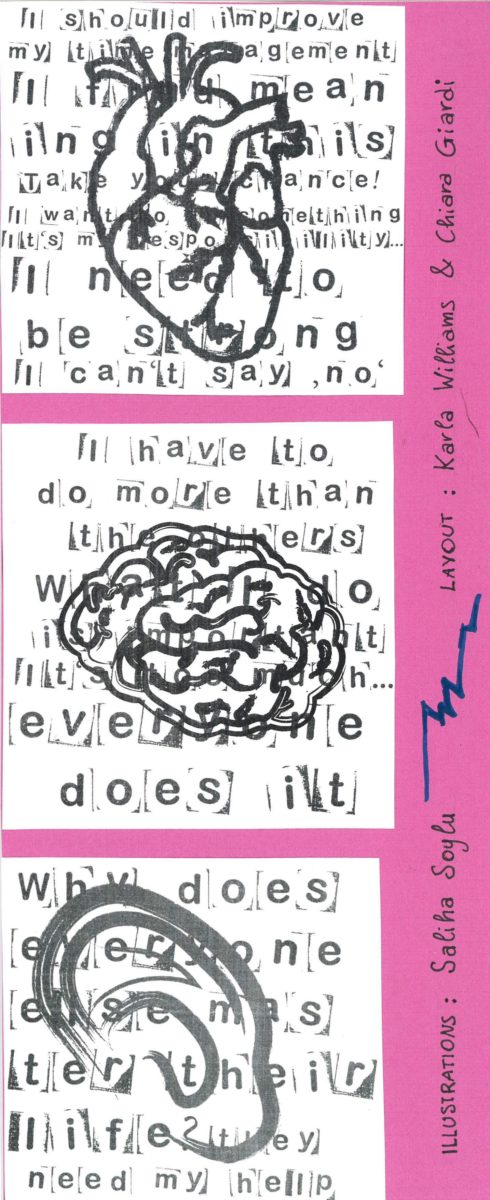

In 2016, more than 40% of all German citizens above 14 years volunteered in their free time (Die Bundesregierung, 2016). Many university students do, too. When listening to peers, for example to me, you will hear a lot about how stressful their lives are. Because I am one of them, I know that this stress is often not caused by university obligations, but rather by a combination of studying and working, friends and family, hobbies and voluntary work. For me, the latter is often even the biggest share. It seems irrational that so many people volunteer, especially when referring to the classical approaches of economics. Many devote a lot of time, sometimes even more than is good for them, to their voluntary work. All aspects of volunteering dispute the expectations on human actors that are represented by the model of the Homo Economicus, an economic man: Volunteering is neither narrowly self-interested, nor helps to strive for constant maximization of utility and profit and, hence, is not rational (cf. behavioraleconomics.com | The BE Hub, 2020). However, one will find that “Volunteer Burnout” is an actual phenomenon (Moreno-Jiménez and Villodres, 2010). Many people dedicate an unhealthily large amount of time to their voluntary work that might even lead them beyond personal boundaries up to a breaking point.

Yet, sometimes it seems that volunteering beyond personal boundaries is not necessarily a conscious decision. It happens subconsciously, influenced by behavioral cues from our environment.

This article attempts to look behind the façade of volunteers and their motivation to volunteer to understand why so many people volunteer to such an extraordinarily large amount. To do so, I have talked to seven university students who are all volunteering and have previously made the experience of reaching a point where their volunteering activity felt overwhelming to them. This article has, however, in no way the claim to be representative.

Volunteering can be defined as “the practice of doing work for good causes, without being paid for it” (Cambridge Dictionary, 2020). However, many different definitions are used and there are certain factors that prevent a clear-cut definition.

According to Davis Smith (1999), these dividing factors include the question whether volunteer activities should only be regarded as such when happening for purely altruistic reasons, whether they need to be completely unaffected by peer pressure or social obligations, who should profit from the volunteering activity or how regular and in what kind of setting an activity needs to take place (Roy & Ziemek, 2000, p. 6). One further division of volunteerism could be undertaken by examining the public service function of volunteering (Robinson and White,1997) outline.

While there certainly is a macro perspective on volunteerism, this article will focus on the micro perspective, which asks the question why individuals volunteer.

![“Because my brother said so…”?

“Ja, mein Bruder hat gesagt, ich soll bei der […] Hochschulgruppe

reingucken, weil er da war.“

„Yes, my brother said, I should have a look at […] University Group, because he was there.”](https://www.jack.uni-freiburg.de/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/because-my-brother-said-so-1.jpg)

All but one of the interviewees I talked to were led to start their volunteering activity because of stimulation from their environment. The start of volunteer action was for all participants a combination of the applied effects of the messenger, the perceived norms and default. One main reason to start volunteering was that friends, family or acquaintances were the messenger who asked people to become active and volunteer. They, as credible informants, influenced people’s decision (cf. Dolan et al, p. 266).

Furthermore, it appears like the norm to volunteer because people form one’s own personal social environment are already volunteering. This norm is then constantly mirrored because you will most likely make new friends, who are all volunteering. Another effect that appears to be present is that volunteering is a default option, because friends and family already volunteer. Many grew into their volunteering activity after having participated and profited from an activity organized by other volunteers. Therefore, it appeared natural to them to volunteer and it was never out of the question that they would become an active volunteer. While people I talked to acknowledge that they blundered into their volunteering activity, subconsciously influenced by the effects of messenger, norms and defaults, they also emphasized, that they later saw the need for and importance of their volunteerism.

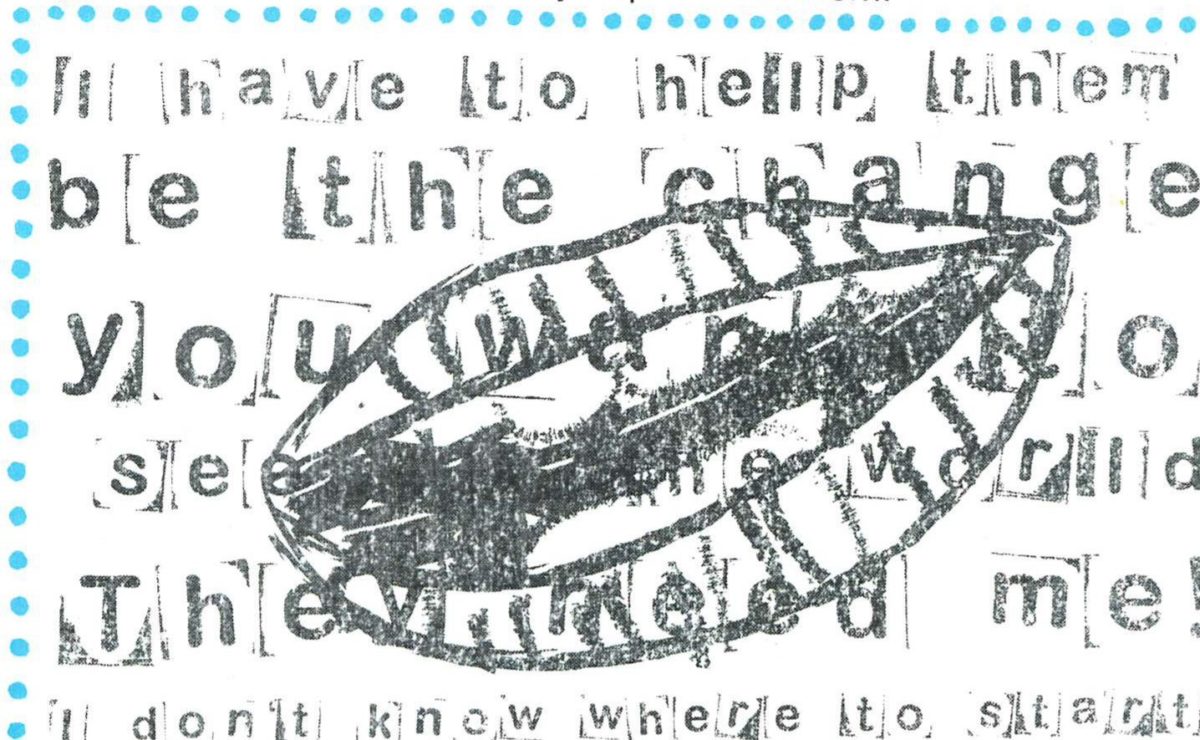

While all people I talked to outlined the wish to change something and an idealistic motive that can be understood as altruistic (cf. Mowen & Sujan, 2005), their volunteering can also be interpreted as behavior caused by affect (cf. Dolan et al. 2012). That means that our decision-making is influenced by an emotional response (Ibid., p.271). One person, for example, outlined that his volunteering activity is a coping strategy to fight against the feeling of powerlessness that the situation in society creates, and that volunteering gives him a right to exist. He also says that he does not actually like volunteering. Subsequently, his volunteering is an emotionally triggered reaction to the current circumstances in society. This observation was also confirmed by another interviewee, who goes as far as saying that he believes that many people are volunteering because they are angry.

According to him, this anger is provoked by realizing the injustice in society, especially through personal experience, but also through educational work. He himself said: „but I noticed how much I wanted to change structures, because I had the feeling that I was only fighting against waves but not against the flood, to speak metaphorically.” [Original: “[…], aber ich habe halt immer mehr gemerkt, wie sehr ich Strukturen verändern will, weil ich das Gefühl hatte ich kämpfe nur gegen die Welle aber nicht gegen die Flut, so metaphorisch gesprochen.“]. Both, what he said about anger as motivation and his personal experience, can be closely connected to the effect of salience: people become angry and start volunteering because their attention is drawn to injustice (cf. Dolan et al, 2012, p.269). And his attention, while trying to help individuals, is triggered by structural problems. Overall, salience and affect seem to work together regarding the stimulation of volunteerism.

Two other effects that also appear to stimulate volunteerism are commitment and incentives. The component of commitment is on a level of sense of duty towards society, the incentives seem to be on a similar level: The incentives are not regarding wealth or gain in money. Instead a reference point, a status quo of society, is identified regarding, for example, equality. This status quo is perceived as unsatisfying which is closely related to the notion of affect within volunteerism. All participants want to be able to change this status quo in society. Accordingly, their incentive is to change the world.

While volunteerism as such might already be a contradiction to classical economics, the fact that people volunteer up to a point where they reach their personal boundaries poses an even stronger contradiction. The reasons that individuals act in this way vary and can, hence, be explained by different influences. These are the planning fallacy, the effect of commitment and the effect of ego. All three effects are intertwined with one another.

![“Ich befinde mich in einem konstanten Kaum-Zeit-Kontinuum […]“

“I am in a constant Scarcely-Time-Continuum […]”](https://www.jack.uni-freiburg.de/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Raum-Zeit-Kontinuum-1.jpg)

One of the reasons why people feel like they have reached their personal boundaries is stress. This stress is created by not having enough time for all the things one needs to do, the volunteering activity only being one part of a whole. This might be identified as a typical planning fallacy (Kahneman and Tversky, 1979) which belongs in the category of optimism biases: The time or resources (e.g. effort or energy) that are needed to fulfill a certain task, here the volunteering activity, is underestimated (Kahneman and Tversky, 1979).

However, it can also be a planning fallacy in the time for preparations. Moreover, the factor of stress can also be related to a planning fallacy within the group that is not necessarily time-related but due to malfunctional committees or organizations. One person, for example, named an insufficient and unjust assignment of tasks within the group. Another interviewee outlined how exhausting it is to constantly criticize and attempt to alter things but nothing changes.

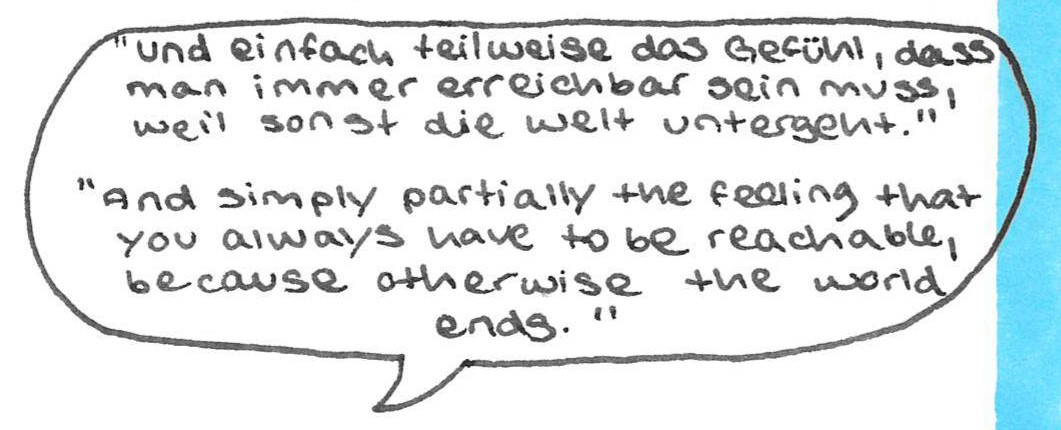

The previously mentioned problem of malfunctional organizations appears to be closely related to the level of commitment that motivates people to keep up their volunteerism but at the same time also gives individuals a feeling of being overburdened. Commitment means that individuals seek to be consistent with their public promise (Dolan et al., p.271). Because of their commitment, individuals do not want to leave a group or reduce their voluntary activity, because they feel like the volunteering activity depends on them.

Some individuals might also feel pressured to uphold their commitment to volunteer because the people they care about and which are perceived as credible messengers also demand a lot of them and expect them to move their personal needs to the back. Furthermore, the personal environment might be upset because individuals do not communicate their feeling of being overburdened well and their absence is perceived as being absent without excuse. This social effect of the messenger might be strengthened by the default tendency of volunteers to agree to voluntary tasks out of habit instead of actively saying no. To actively say no can, conversely, be the solution to avoid the feeling of reaching personal boundaries for many volunteers.

![“[…] sondern da kann man sich auch einfach mal ein bisschen hassen,

dass man das nicht hinbekommt.”

„[…] instead you can also simply hate yourself a little bit, because you were not able to accomplish it.”](https://www.jack.uni-freiburg.de/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/hassen-1.jpg)

The fulfillment of their commitment aligns with the ego effect that stands for the action of individuals to improve and mend their self-image. The feeling of crossing one’s own personal boundaries can, thus, be created when confronted with one’s own shortcomings. As an interviewee states, this can even lead to self-hatred. Another participant also talks about his expectations of himself and how these are influenced by the pressure to represent the people who voted for him in the city council election.

He expects from himself “to be at least the best politician or the best person that I could have been or can be in the future.” [Orig.: “zumindest der beste Politiker oder der beste Mensch sein zu können der ich hätte sein können oder in Zukunft sein kann.“]. These expectations, furthermore, lead to the fear of failure and making mistakes.

Through the interviewees I conducted, I understood how volunteering behavior is strongly influenced by the environment. Not only the starting reasons for volunteerism are influenced by these effects, but also the reasons why people get to a point where they feel like they reached their personal boundary and the reason why they keep up their volunteering activity even when they cross this point. This can help both volunteers themselves and society to understand volunteerism better and to develop coping and support strategies in this field.

Yet, a question I have also asked myself is where this leaves me? Where does this leave the volunteers? In practice, we must work on ourselves to be healthy and to avoid breaking apart because of our volunteering activity. What might sound easy is hard to implement. A core element is to reflect on the reasons why we volunteer and what motivates us to spend a lot of time on our volunteering activity. Furthermore, we should try to plan in some extra time in our regular schedules to balance out possible mistakes due to the planning fallacy. Most importantly, we are not perfect, and the world will keep spinning when we fail. But, now and again we just have to let people tell us or tell ourselves: Give yourself a break!

![References:

behavioraleconomics.com | The BE Hub. (2020). Homo economicus. [online] Available at: https://www.behavioraleconomics.com/resources/mini-encyclopedia-of-be/homo-economicus/ [Accessed 7 Mar. 2020].

Cambridge Dictionary. (2020). VOLUNTEERISM | meaning in the Cambridge English Dictionary. [online] Available at: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/volunteerism [Accessed 7 Mar. 2020].

Die Bundesregierung (2016). Ehrenamtliches Engagement gehört zum Alltag. [online] Die Bundesregierung. Available at: https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-de/aktuelles/ehrenamtliches-engagement-gehoert-zum-alltag-387050 [Accessed 7 Mar. 2020].

Dolan, P., Hallsworth, M., Halpern, D., King, D., Metcalfe, R. and Vlaev, I. (2012). Influencing behaviour: The mindspace way. Journal of Economic Psychology, 33(1), pp. 264-277.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Intuitive prediction: Biases and corrective procedures. TIMS Studies in Management Science, 12, 313-327.

Moreno-Jiménez, M. and Villodres, M. (2010). Prediction of Burnout in Volunteers. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, [online] 40(7), pp.1798-1818. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/229800804_Prediction_of_Burnout_in_Volunteers.

Mowen, J. and Sujan, H. (2005). Volunteer Behavior: A Hierarchical Model Approach for Investigating Its Trait and Functional Motive Antecedents. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 15(2), pp.170-182.

Roy, K. and Ziemek, S. (2000). On the economics of volunteering, ZEF Discussion Papers on Development Policy, No. 31, Bonn: University of Bonn, Center for Development Research (ZEF).](https://www.jack.uni-freiburg.de/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/references-1200x750.jpg)